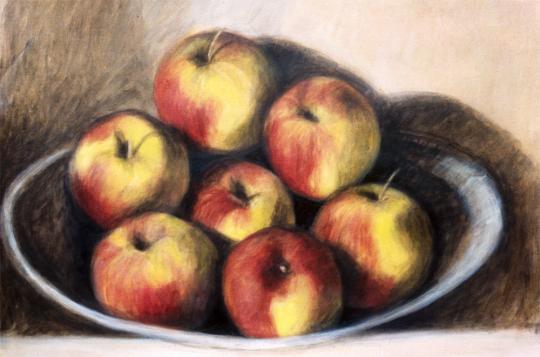

The Seven Apples

I don’t want to be called a sissy," said Melwood as he threw his cap down in the corner. "Please, Mother, let me go on a hike with the gang tonight. Chuck isn’t as bad as you think. He’s the best leader we’ve ever had."

Melwood frowned as Mother said firmly, "No, son, I would rather you didn't go. Just forget about the hike. And please bring up a pan of apples from the basement."

"OK," said Melwood. "How many shall I bring?"

"I want six of the nice red Jonathans. You may fill the pan up with the others."

Melwood placed the six red apples carefully in the bottom of the pan. They fit exactly. Then he took some of the spotted ones that Mother used for sauce and pies, and brought them up.

"Thank you, son," she said, smiling as she removed all but one of the cooking apples to another pan.

"That one you left is too spotted for baking," said Melwood. "Shall I get you another good one for the middle?"

"I'm not going to bake these this time. I shall keep them on the shelf for another purpose. We will leave these seven just as they are in the pan."

Melwood thought it strange, but he put the pan on the shelf as Mother directed.

Two weeks passed. The gang, under Chuck's leadership, had taken two more hikes. The vivid accounts of the fun they'd had were almost too much for Melwood. In the stillness of the study period he could almost hear his pulse throb as he reread the note from Chuck: Why do you always have to listen to your mother? Why do you have to tell her everything? Sissy! We'll be down on Third Avenue waiting for you at 7:00 sharp. If you don't come this time, just consider yourself out of the gang. Chuck.

"Out of the gang'sissy'why tell Mother?" Melwood never kept any secrets from his mother. She was his best pal, even though she didn't approve of the gang. Perhaps she was jealous and wanted him all to herself; maybe he was a sissy after all! Well, he would show them he wasn't a sissy. He would still be in the gang.

When the dismissal bell rang, Melwood closed his history book, crumpled the note from Chuck, and slipped it into the wastebasket as he walked out. Chuck was waiting for him at the foot of the stairs. "It's your last chance, you know, to be in the gang," he said.

"OK, I'll meet you at 7:00. I'll show you I'm not a sissy."

Mother was concerned about Melwood that evening. He was so restless and kept watching the clock. Finally he told her he had a headache and went to his room.

It was 6:40. Mother was busy in the kitchen washing dishes. Now was his chance to slip out. Would she become anxious about his headache and come into his room and find him gone? Well, she would know he wasn't a sissy anyway. He was still an active member of the gang.

The boys were all waiting on Third Avenue when Melwood arrived.

"Hi, Mel!" they greeted.

"Hurrah!" said Chuck. "We knew you weren't a sissy. Come on, gang; we're headed for the old mill!"

Away went the boys, with Chuck in the lead. After exploring the old building for several minutes, they gathered in the room that had once been the office, to await instructions from Chuck.

"Let's light up first, then get down to business." Taking a package of cigarettes from his pocket, Chuck passed them around to the six boys.

"I don't smoke," said Melwood. "Thanks just the same."

"You don't smoke!" echoed Chuck with a sneering laugh. "Aw, come on, you'll get used to it'we did. It takes more than one drag to make a man out of a sissy, you know."

"Well, all right, give me a light."

It didn't require many puffs to produce a real headache. What would Mother say if she could see him now? What would Dad say? Dad didn't smoke. Was Dad a sissy?

Melwood didn't like Chuck's jokes, either. In the midst of a big laugh, Melwood slipped outside for a breath of fresh air. He did not like the choking sensation in his throat. If that was what the gang called fun, he would rather be called a sissy. They were still laughing in the office'they wouldn't miss him.

Mother was still in the kitchen when he entered the house. Did she know he had been gone?

Suddenly on the still night air came the sound of the fire siren. Mother went to the window to watch the fire trucks passing down Third Avenue.

"There must be a fire at the old mill," said Mother in a subdued voice. "I can see the red glow and the smoke in that direction."

The old mill! Melwood buried his face in the pillow and tried to think. How did it happen? What if Chuck and the gang were still in the old office? No, they surely got out in time. He wanted to watch the fire from the window with Mother, but she would smell his breath and know he had been smoking. Anyway, his head really did ache terribly now; he would rather stay in bed.

The next morning Melwood's head still felt dull and heavy, but he went to school. The fire at the old mill seemed to be the main topic among whispering groups. Melwood occasionally heard bad remarks about the gang members. What if someone told the officials that he had been with them? It would break Mother's heart if he were sent to reform school. That would be far worse than being called a sissy.

Melwood went with a number of children after school that evening to view the ruins of the old mill. It was a total loss. Nothing remained but a few charred bricks and ashes. What if it had been his cigarette that had caused the fire?

Mother was taking a pie out of the oven when Melwood returned home.

"Oh, good, apple pie for supper!" He hung his cap on its proper hook and began to give an account of the mill fire.

Mother seemed to know all about it. She even supplied him with additional information.

"How do you know so much about the fire?" Melwood asked.

"An investigator called this afternoon, thinking you had been with the gang last night. I told him he was mistaken, that you had been at home with a headache and that you were no longer a member of the gang. I'm afraid Chuck led the boys into serious trouble. Will you get that pan of apples that you put on the pantry shelf some time ago? I think we can use them now."

A swarm of tiny fruit flies arose as Melwood placed the pan of apples on the table. The once-spotted center apple was now hopelessly withered and brown. A brown spot appeared on each of the rosy ones where they had touched it.

Mother didn't say a word as Melwood thoughtfully gazed into the pan. She put her arm across his shoulder, and he put his arm around her.

"Now I know why you saved this pan of apples, Mother. It was to show me what Chuck was doing to our gang."

Then he told her of his decision at the mill, and how he would rather be called a sissy all the rest of his life than to be a member of that kind of gang.

Mrs. John F. Underhill

- Home

- Days Of Long Ago

- Farmer

- Cougar

- Three Men

- Dog

- I Will Return

- Esther

- Joseph Bates

- Martyr

- Courage And Strength

- The Dark Cloud

- A Prayer In The Dark

- Sabbath Of The Lord

- Kingly Shepherd Boy

- Man In The Philippines

- Heart Searching

- Companion In Trouble

- Book

- Willie

- Jonah

- Kitten and Cobra

- From Above

- Preacher A Thief

- Jolanta

- Glass Of Milk

- Dangerous Ice

- Marge

- Train Wreck

- Happy Family

- Beware

- What Next

- Revenge

- Preacher

- Thankful

- Angel By Me

- One Cord

- The Record

- Decision

- Susie Prayer

- Company Manners

- Company

- The Ballroom

- Make Plain

- Christ Our Refuge

- Slaughter

- Toms Trial

- Premium

- Caravan Starts

- Kind Word

- Another Commandment

- Retired Merchant

- Novel Reading

- Just Before Generous

- Quicksand

- Light In Darkness

- What Shall Profit

- Within Your Means

- Wrong Pocket

- My House Our House

- Mountain Prayer Meeting

- Rescue At Sea

- Only A Husk

- Ruined

- Was Blotted Out

- Never Indorse

- A Life Lesson

- Hard Times Conquered

- Good Lesson Spoiled

- Prayer For Pirates

- Grandmothers Room

- School Life

- Benevolent Society

- Instructive Anecdote

- Didnt Smoke

- Scenery Trip

- The Young Musician

- Lymans Testimonial

- Unforgotten Words

- Herrings For Nothing

- Bread Upon The Waters

- Miracles In Africa

- Rift In The Cloud

- Reward Of Perseverance

- Ricest Man

- Over The Crossing

- Mother Prayer

- Fence Story

- Drugs And Why

- In My Place

- Infidel Captain

- Jewels

- Nellie Altons Mother

- Dangerous Doors

- Heart Has Sorrow

- The Open Door

- Weeping

- Evening Prayer

- Happy New Year

- Rowena And Pills

- Scripture Quilt

- Speak To Strangers

- The Lost Bag

- Fire

- The Majors Cigar

- Creation Story

- Little Sisters

- He Stood The Test

- Widows Christmas

- A Will Joe

- Large Oak Tree

- Scene In A Saloon

- Look To Your Thoughts

- Andys Hands

- For Whom

- Infidels Converted

- The Perfect Helper

- Arrested For Christ

- Twenty-Three Miles

- Left To Die

- Boy Of New Guinea

- Winifreds Party

- Fjord And Ferry

- Working With Him

- Clock Struck Thirteen

- Kant And The Robbers

- Can And Could

- Wormy Puffball

- Neds Trust

- King Snakes

- Maggies Lost Cat

- Act Of The Will

- Home For Harry

- Set Free

- Door To Door

- Hard To Reach

- Reaching A Muslim

- Bears

- Bushman story

- Milk Pan

- A King Is Born

- Hailstorms And Horses

- The Unbeliever

- Man With A Past

- Disarming Dog

- Broken Bone

- Angel Over Tent

- Cow Got Stuck

- Brave Girl

- Boat And Raft

- Battles

- Taking My Picture

- Moderation

- Miss Clancy

- School

- Golden Gate

- Morning Star

- All The World

- Mountain Children

- Six Years Old

- Greatest Gift

- God's Love In Affliction

- Zacchaeus

- Letter From China

- Angel Hand

- Angry Mob

- A Daughter's Prayer

- Deliverance

- Dog That Watched

- Footprints In Snow

- Prayer Of Faith

- Urgent Voice

- Watchmen

- Where's Your Friend

- Never Give Up

- By The Window

- Little Lamb

- Sea Stars

- Good Foundation

- Wandering Glider

- Tough Roots

- Trust Jesus

- Build A Bridge

- Oilbirds

- Potatoes

- Honeybee

- Stormy Night

- Shabbat In Lvov

- Hospitality

- Alone With Wolves

- Elephant Lifesaver

- Angel's Hand

- Angel On Patrol

- In The Night

- Sierras

- Someone Helped

- Mission To Portland

- Food From Heaven

- Sticky Situation

- Taking The Bite

- Soldier For God

- Beriberi Good Discovery

- Who Is King

- Rescuing Uncle Nat

- Modest Abe

- In The Mist

- Baton Rouge

- Baby Craze

- Miracle Water

- Out Of Control

- The Back 9

- The Bull Preached

- Speed Toward Trouble

- Miracle In Boston

- Bandits In The Night

- Nailed

- Arrested For Jesus

- Dog Sold A Book

- Enemies

- My Shoes

- Kidnapped

- Emergency

- Money Trouble

- Friends For Real

- Prickly Revenge

- Paper Carrier

- Baby Elephant

- Silent Culprit

- Triple Blast

- Strange Idea

- Seven Apples

- Crack In The Wall

- Miracle For Melianne

- Meet My Brothers

- In The Field

- Jellyfish

- Greetings From Florida

- Trapped In An Oven

- Outnumbered

- Kingdom Of Ants

- Rustlers

- Cornmeal Answer

- Awakened By Rattlesnake

- Meerkats

- Christmas Plan

- Stampede

- Saving Twins

- Dead Man Talk

- Hurricane Warning

- Treasure In Wales

- Test Of Faithfulness

- Fernando Stahl

- Grouchy Mrs C

- Behind Enemy Lines

- Buried At Sea

- Miracle In The Surf

- Charming Nancy

- Mountain Of Fear

- Trail To Freedom

- Forbidden Village

- Leather hat

- Midst Of Danger

- Jungle Missionaries

- Bluebells

- Call To Kayata

- Gossip Story

- We Have Hope

- Kindness Repaid

- Cuttlefish

- Rescued

- Little Child

- The Potter

- Hands

- Willie's Story

- Kindness Of A Stranger

- Kindness Pays

- My God Hears

- Freedom's Shore

- Light In The Darkness

- Robbers Repent

- Datu's Dream

- Helped By An Angel

- Freedom In Jesus

- Peace In Jesus

- Convert

- Changed Heart

- A Child's Song

- Fasting

- Escape

- God's Money

- Vision Of Love

- Just A Minute

- From A Friend

- Power Of Influence

- Bouquet Of Gods Love

- Divine Love

- Caught By Christ

- God's Wings

- Little trees

- Stuck In The Closet

- Mad Dog

- Lone Flight

- Becky's Flowers

- Drummer Boy

- Crossing The Street

- Fire Chief

- Clock Struck Ten

- Earthquake

- Sold

- Where's The House

- It's Broken

- Rain And Flood

- Vacation Brakes

- The Very Smallest

- Angel Power

- Delayed Not Denied

- Two Chairs

- Count And The King

- No Theology Degree

- How The Prophet Felt

- Unsharpened Knife

- Horse Sense

- Prayer Is Real

- Learn Instantly

- Little Indian

- Heaven's Guard

- In Advance

- Three Dreams

- Father Knows Best

- Voice Of An Angel

- Across The World

- Without Leaving Home

- Tiger On The Trail

- Sharpened By Sword

- The Unseen

- Shoe Repair Shop

- Telegraph

- Two-Week Hideout

- Liberty

- King And The Girl

- Busy Spider

- Dogs And More

- Brave Man

- Protecting Hand

- Lost Carabao

- Poisoned In Tibet

- She Loved Her Lord

- The Letter

- Angel In A Boat

- Believing Prayer

- Touch Of Angel Hands

- So Many Lights

- An Ant Did It

- Big or Little

- How Much Water

- Shingles

- Miracle In India

- Night Visitor

- Without Realizing It

- Six Little Girls

- Home Invasion

- Only One Key

- Thunder At Eight

- Credentials

- In The Fire

- Grace

- Fire Inferno

- Gave Mother A Message

- Granny Gets Baptized

- Kirkland

- All She Suffered

- Chinese Adventures

- Twice Delivered

- Africa

- Labor Of Love

- Map On The Wall

- New Year Connecting

- Gentle Giant

- A Prisoner

- Prayer

- God's Power

- Raised Spear

- New Church

- Exciting Work

- The Great Physician

- Track Indians

- Perseverance

- Honest Confession

- Delivered From Alcohol

- The Wanderer's Prayer

- Singular Will

- Inspiration In My Work

- Ears That Hear

- Stepmother

- Colporteurs

- When Mother Is Gone

- Expected Miracle

- God Is Not Mocked

- Survive A Freezing River

- Hell On Earth

- With The Green Cover

- Bad News

- The Stowaway

- Power In God's Word

- Grandfather's Faithfulness

- Foes Or Friends

- Challenged Me

- Deadly Combination

- Face Death

- Journey To Happiness

- Keep It Holy

- Animal For Children Story

- Almost

- Hand Of God

- Never Let Go

- Could Have Been An Angel

- God And The Spider

- A Plucky Boy

- Strange Mechanic

- This Moses Was Black

- Relay For Life

- Angel Of Mercy

- Thanksgiving

- Buzzing Sounds

- Paid A Debt

- Morpho Butterflies

- Crutches On The Alter

- One Boy Did

- Don't Get Burned

- Save The Bibles

- Basket Of Coal

- Autumn Leaves

- Carl's Garden

- Courageous Visitor

- Miracle In The Mountains

- Amazing Orchids

- Good Neighbor Policy

- The Lord Will Provide

- Isaiah 53 5

- Playing For The King

- One Minute More

- Small Corners

- Surprise Package

- Child Shall Lead Them

- Guards Of The Lord

- The Winds Blow

- Snapping Turtle

- Three In A Row

- Tweety

- Coals Of Fire

- Chicken House Snake

- Love

- The Kinds Of Bears

- Moses The Cat

- Lost Not Forgotten

- Feathers

- Missionary Spirit

- Emperor Penguin

- The Brown Towel

- God Will Take Care

- A Prayer Weighs

- The Golden Windows

- Worship The Devil

- Myrmecophytes

- To Be Caught

- Tree Frogs

- Feathered Jewels

- Called To The Light

- Baby Duck

- The Big Six

- Birthday Card

- Rescue At Night

- Fish Cleaning

- Fishing

- Dragons

- Chain Gang

- Troglomorphic Fish

- Mother's Love

- Mammalian Aviators

- Ocean Giants

- Tom's Revenge

- God Is Seen

- Spare Moments

- Shorebirds Talents

- Cobra In The Closet

- God Made Me Too

- The Choice

- Shining Face

- Taking Aim

- And I Wept

- Latchkey Was Out

- God Made Wonders

- The Kitten

- Don't Go To Church

- Rajeshwari

- Manna From Heaven

- Red Marbles

- Attractive But Deadly

- Boardman's Deliverance

- Escape By Prayer

- Deliverance Of Clarke

- God's Mercy

- Does A prayer Weigh

- Something Better

- Make An Overpass

- Laddie The Leader

- Book Mobile

- Shut Up With A Bible

- Tripped By An Angel

- Martyr's Mirror

- Muriel's Bright Idea

- The Ship's Crew

- A Stormy Night

- Strength Of Clinton

- Three Stages

- Trapped

- A Favorite

- Mother's Day Disaster

- The Little Latchkey

- Stuck On The Mountain

- Learned To Pray

- Faith That Never Dies

- On The Road

- Martyrs For Jesus

- Errand Boy

- Killer Bees

- Beautiful Farm

- Put To Flight

- Hurricanes

- Relief Of Leyden

- The Christian Dog

- Angel Report

- Persecutor To Persecuted

- Charles Tells His Story

- Love Story

- Grandma's Birthday

- Prepared Heart

- Revolution

- Lady In Japan

- Bandidts

- Lightening

- By Tempest

- Pray To Jehovah

- Elements Overrule

- Widow And The Priest

- Turning The River

- Trusting Jesus

- Happy Home

- Mad Elephants

- One Black Spared

- Christian Mechanic

- Bible And Magic

- Children Poems

- Siberia

- Stories

- Narrow Escape

- Interposition

- Pushed The Car

- Tennent In A Trance

- Have A Nice Weekend

- What Love Can Do

- Angel's Work

- Forbidden Book

- Jimmy And Grandpa

- Katie's Tongue

- Mabel's Dream

- Maple Syrup

- The Long Road

- Things That Spread

- Love Your Enemies

- Vision

- Boy And His Boarder

- Dog Saved A Crew

- Prison Door Open

- A Boy Lived Again

- God Chose One Weak

- Anne Askew

- Zinzendorf

- Hottentot Boy

- Cry For help

- Livingstone

- Elements Work

- Fugitives Delivered

- Forsaken Idol Tree

- Chinese Heart

- Out of Darkness

- Steps Of Faith

- Get The Captives

- Help In Formosa

- In Pondoland

- Boxer Uprising

- Basuto Raiders

- Flash Of Lightning

- Providential Gale

- Deliverance In Nicobars

- Restraining Hand

- Friends For Jesus

- Special Project

- Did Not Laugh

- Radio Station

- Run To Church

- Curious Carla

- Mango Tree

- Louisa's Lunch

- Red Motorbike

- Refuse To Pray

- Mopane Tree

- No Longer Bored

- Runaway Goats

- Letter From God

- Sad Little Duku

- Basile's Discovery

- Singing Band

- Boy's Witness